No Happy Endings, Just Real Ones: How Gen Z is Reshaping Broadway

With stars like Sadie Sink and storylines that reflect the complexity of young adults’ lives, a new wave of Broadway productions is resonating with younger audiences.

This summer, The Up and Up is fortunate to have two stellar interns contributing to our growth and strategy. Kate Hoffner, a rising junior at Vassar College, joins me in co-writing today’s edition. Kate was instrumental in the planning and writing of today’s newsletter, and her take on John Proctor Is The Villain is featured below. But first, a note from me.

I saw John Proctor Is The Villain on Broadway last week and can’t stop thinking about it. Not only can I not get Lorde’s Green Light out of my head (more on that below), but the play, which offers a very 2025 take on a very 2018 theme, is incredibly powerful. With a cast that included Gen Z icon Sadie Sink (through last weekend) and a script that reads as though it could have taken place in any classroom across the country during President Donald Trump’s first term, the play, written by Kimberly Belflower, offers a window into the fact that Broadway is having a Gen Z moment.

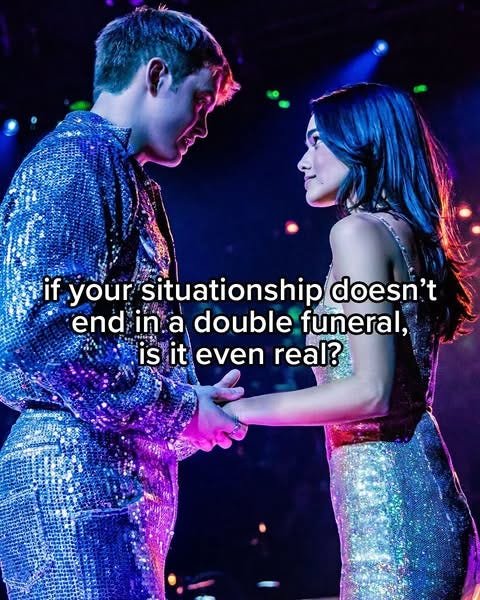

Let’s rewind for a minute. Romeo + Juliet made a splash with its Broadway debut last year, thanks in part to smart casting (including Kit Connor and Rachel Zegler), modern costume design, and a Gen Z-savvy social media presence. With Gen Z-coded advertising and its ‘The youth are f*cked,’ tagline, the musical employed tactics like having influencers take over the show’s Instagram and TikTok feeds to reach a younger audience. According to the AP, 14% of Romeo + Juliet’s ticket buyers were 18-24, a steep jump from 3% of all Broadway tickets.

Make no mistake about it, this audience is looking for stories that feel real, and these shows level with young adults, without happy endings.

To make sense of how Gen Z is reacting to both of these shows, and how Broadway as an industry is meeting Gen Z audiences, I spoke with Anna Mack Pardee, Producer at Seaview, the production company that brought Sam Gold's Romeo + Juliet to Circle in the Square Theatre this past fall.

When it comes to Romeo + Juliet, Mack Pardee said the show’s director, Sam Gold, was intentional from the get-go about focusing on this Shakespearean classic speaking to a younger generation. In fact, she said, Gold approached the show as though there was “a group of kids that broke into Circle in the Square and had to put on a show to express their feelings, and that show just happened to be Romeo + Juliet.”

Here’s our conversation, edited for clarity and brevity.

Extrapolating from the success that you had with Romeo + Juliet, what patterns are you seeing in how Gen Z shows up for Broadway?

At the first preview of Romeo + Juliet, I remember standing in the back of the house and seeing all of these young women in particular and thinking, ‘Oh my god, I have never seen an audience like this.’ I mean, they were screaming and so excited to be there. They showed up, bought tickets at premium prices, and were completely engaged.

A testament to the fact that, if the thing is good enough, and they feel like they're being spoken to, they will come.

The whole experience really opened the door to a new audience and allowed for them to see themselves in other productions like John Proctor and more shows that are coming to Broadway next season.

What kinds of stories and themes do you see resonating most with Gen Z on Broadway right now?

I find that when Gen Z sees themselves represented, there’s a connection. So, in terms of R+J, whether it was them being captivated by the music that we were playing at the top of the show, or the costumes that our cast were in, or relating to the feeling of being in love for the first time and grappling with those feelings, they got to witness a piece of themselves on that stage. In John Proctor, one of my favorite through lines in the show is the female friendships and how well these young women support one another. That's a reflection that young audiences can relate too.

How did Gen Z’s digital fluency and the social media environment shape your marketing for Romeo + Juliet?

It was us as producers and as an older generation relying on and trusting the younger people that we work with. I very much was open to and excited by all the ideas that they came to us with.

I really followed their lead when it came to how to write new copy, or what photos were going to work, or what memes were going to work, or how we were going to comment back to people that were commenting on our posts. I wanted us to allow for the young people that were working on the show, behind the scenes, to drive the communication with the people their same age who were seeing the show.

There were a lot of touch points and cultural references for Gen Z that were constantly mentioned during the campaign, leading with incredible visuals paired with beautiful photos to grab their attention.

How does the Gen Z Broadway audience differ from prior generations of young people? Does the Gen Z audience differ from the millennial audience when they were their age?

I think about what was coming up when I was in my early twenties, and I do think the shows that are speaking to Gen Z now are different from what was speaking to me then. Shows are a bit bolder, we’re saying a bit more not just in the context of the plays and musical themselves, but in all touch points of the piece of work. It’s no secret that we’re living in very trying times at the moment, and Gen Z is at the forefront of talking about that. I don’t think that I’ve ever seen a generation be so politically active in demanding what they want to see from the world. The shows that we’re seeing now come off of that moment in society both politically and culturally.

Something that comes to mind, is a bit early millennial, but it sort of reminds me of when Rent or Spring Awakening came out. Those early aughts and the 90’s productions were really boundary pushing. I do think every generation has its moment with the art form in response to what the young people in the world are feeling. But there’s a little bit of anger and motivation behind the work that’s being produced right now. That’s really powerful, and I think that comes from Gen Z's adamant and demanding hope and need for a better future.

The best way to understand how young people feel about something is to hear directly from them. That’s why I was so excited when The Up and Up’s summer intern Kate Hoffner told me she wanted to write about John Proctor Is The Villain. Her take not only highlights why the show is connecting deeply with her generation, but also gives a firsthand look at how Gen Z is engaging with Broadway. I learned a lot reading it and think you will too. We tried not to give any spoilers… Here’s Kate’s piece:

‘John Proctor Is The Villain didn’t feel like a play set in the past, it felt like my own memories’

The language, music, and tone of John Proctor Is The Villain captured exactly what it felt like to be a teenage girl in 2018. It didn’t feel like a play set in the past, it felt like my own memories. For young women like me, the show hits home. The cast looks like us. The dialogue sounds like us. Sadie Sink, who plays one of the lead characters, is a prominent Gen Z actress that so many of us admire – not just for her roles, but for the way she brings honesty and depth to young, complicated characters. Her presence helped center the story in our world.

Set in a high school English classroom in rural Georgia in 2018, the students in John Proctor Is The Villain are reading The Crucible, trying to make sense of the ways women have been silenced for centuries, while, at the same time, living through their own version of it. The 1950s-era play about a 1600s-era problem is all too familiar. As the #MeToo movement gains traction outside their school walls, it starts to seep into their everyday lives. Personal relationships are tested, long-held beliefs are challenged, and what starts as classroom discussion turns into something much deeper: a raw, nuanced story about trust, complicity, and the courage to speak up.

In 2018, I was in eighth grade. I had started to understand what it meant to be looked at a certain way, touched without consent, or made to feel small in situations I didn’t yet have the language to name. That year was a turning point – not just publicly, as stories of assault and misconduct flooded headlines – but privately, in the quiet spaces where girls were realizing they were allowed to be angry. Allowed to say no. That their discomfort was valid. I know girls like those in the show, they could have been my older sisters, or cousins. Their experiences didn’t feel like fiction; they reflected conversations I’d overheard or had in real life. And their characters are so relatable, through their language, mannerisms, and shared trends.

The way the characters joked, argued, deflected, and opened up – it was so Gen Z. They referenced pop culture the way we do, not for show but as shorthand for emotion. The dialogue had that specific Gen Z rhythm: fast-paced, emotionally layered, jumping from humor to heartbreak in a single sentence. Even the way they navigated group dynamics, sarcasm, and that awkward mix of confidence and vulnerability was spot on. It drove home the fact that sometimes representation isn’t just about telling a certain story, it’s about getting the voice right too.

Now I’m entering my junior year of college, and I’m only just beginning to grasp how deep the experiences portrayed in the show run. The fear, the second-guessing, the internal calculations we make just to stay safe follow us into new stages of life: into dorms, workplaces, relationships. John Proctor Is The Villain didn’t just remind me of that, it pulled me right back into it. And while the events of the play are quite specific and extreme, the emotional landscape is strikingly familiar.

Female friendships are core to the play’s story arch and part of what makes it so intimate and emotionally resonant. At a climax in the show, a conversation between two young women represents the significance of being met with trust instead of skepticism. Their back-and-forth captured the closeness, protectiveness, and subtle or not-so-subtle tension that can exist in those relationships, the way girls so often become each other’s safest place in a world that doesn’t always listen to them. Watching these bonds onstage, I recalled the people in my own life who’ve shown up for me in quiet but big ways, and how much that kind of support can mean.

After growing tension, the final scene of John Proctor Is The Villain offered something different: release. These two characters, who had been at odds throughout the story, presented their class project (which was to write their own scene of The Crucible). Lorde’s ‘Green Light’ was central to the show’s plot, and it was the soundtrack to their final project as they danced to the pop anthem. The lights shift, the tension finally breaks, and there’s a moment of freedom, of defiance and joy. It wasn’t about forgetting what happened. It was about reclaiming agency after all the pain.

The first time I heard “Green Light,” I was in the car with my older brother and best friend, driving across the Golden Gate Bridge with the windows down, blasting it at full volume. Later, during Covid, I’d play it alone in my bedroom, dancing in circles, trying to shake off the weight of isolation and angst I felt at the time. It’s one of those songs that has followed me through so many versions of myself. Hearing it fill the theater, watching the characters move and laugh and come back to themselves, I felt it deeply. As the audience swayed along, I realized how many of us shared that experience. That scene, two girls dancing to Lorde in a classroom full of anguish and survival, felt like a quiet revolution. And in a way, it was.

Surely, this show brings Gen Z to Broadway. But it’s not just for my generation. What was even more moving that evening was who I was with: my mother and grandmother. Three generations, sitting side by side, watching a story that managed to reach each of us. We’ve all lived through this in different ways. Different eras, different norms. And yet, this play cut through all of that. It reminded me that these patterns didn’t start with me, and they won’t end with me either. But there’s something meaningful about facing that truth together.

When the lights came up, I wasn’t the only one crying. All around me were people my age, wiping their eyes, still absorbing what we had just witnessed. We’d each brought our own experiences into the theater, but in that moment, we shared something collective. That kind of recognition and sense of community doesn’t happen often, and that’s what makes Broadway, in this moment, so special.

John Proctor Is The Villain isn’t a tidy story. It doesn’t wrap things up neatly or offer closure. Instead, I found that it lingers in the gray areas. And that felt honest because that’s where so many of us in Gen Z have lived. We’ve grown up in a world that’s never really slowed down, from one crisis to the next. Even before we had the language to name it, there was always a sense of urgency, of instability, of being asked to process things that felt too big, too heavy, and too fast. This play captures that feeling, the overwhelming chaos of being young in a world that never lets you feel at peace. It asks hard questions: What happens when someone you love does something you can’t defend? How do you speak up when you’re still unsure of what happened? What does justice actually look like when you're young and scared? The show doesn’t pretend to have answers. But it offers something else: recognition. It holds up a mirror to the unspoken. The stuff we feel but rarely say out loud. The tension between wanting to protect our friends and needing to protect ourselves. The complicated grief of realizing someone crossed a line. It’s all there. In making space for that complexity, the play reminded me that these experiences aren’t isolated, they’re shared, ongoing, and impossible to ignore.

Noteworthy reads

Gen Z Is the Loneliest Generation at Work, Study Finds, Suzanne Blake for Newsweek

Why We Mistake the Wholesomeness of Gen Z for Conservatism, Jessica Grose for The New York Times

Gen Z men, women have a deep political divide. It's made dating a nightmare., Charles Trepany for USA Today

So many great insights here! For Kate: what do you think the lessons here are for organizations that are resistant to empowering their Gen Z team members to direct content strategy? How can Millennial and Gen X managers help support this shift in action?