‘What are we going to do to move forward?’: From addressing racial disparities in the media to Black maternal mortality rates, students in Delaware describe their hopes for the future

For the past few weeks, I’ve traveled to cities across the country and talked with young Americans as part of a project to amplify Gen Z voice with the Walton Family Foundation and Murmuration.

A note to readers

For the past few weeks, I’ve traveled to cities across the country and talked with young Americans as part of a project to amplify Gen Z voice with the Walton Family Foundation and Murmuration, an education advocacy nonprofit. This week, I visited Dover, Delaware, Miami, Florida, and Atlanta, Georgia -- just one day after the Senate runoff there. More to come on Miami and Atlanta in just a few days…

The conversations are part of a broader initiative to gauge how young Americans are feeling in the aftermath of the 2022 midterms. Did they vote? If so, why? If not, why not? Do they view voting as an effective vehicle for change? What issues matter to them most?

The project will build on existing research from the Walton Family Foundation and Murmuration that has so far explored Gen Z's perspective on civic engagement, work life, family life, education, life preparedness, and more.

The two groups teamed up to start exploring themes and trends pertaining to Gen Z last spring, and now, as a fellow with the Walton Family Foundation’s education team, I have the privilege of joining, observing, and reporting on some of the takeaways.

I hope you enjoy reading about our findings. Please don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions, and we look forward to sharing the final product down the line.

From addressing racial disparities in the media to Black maternal mortality rates, students in Delaware describe their hopes for the future

Last Friday I traveled to Delaware to speak with students at Dover High School and Delaware State University (DSU), a historically Black university.

From concerns over violence, racial injustice, and a lack of race-based studies in the classroom to feeling as though politics doesn’t work for them, the students’ frustration with the status quo was palpable.

And yet, again, they were resolute in their desire for change.

Students with Dover High’s Black Community on Campus Club have organized community meetings with leaders in the district’s administration. All but two of the students at Dover High said they had previously participated in a march, protest, or walk out for issues ranging from Black Lives Matter to abortion rights.

Asked about local issues in their communities, students at both Dover High and DSU immediately mentioned everyday gun violence as an issue in their community. They specified -- not a fear over mass shootings or school shootings, but local gun crime.

“When the streetlights come on, stay in the car,” said one student at Dover High. Another student said they’re afraid to go to parties because of shootouts.

“You’ve just gotta pay attention to your surroundings,” said another Dover High student.

‘The term Gen Z has been stigmatized in a way’

At Dover High, the group of students ages 16-18 rejected the descriptor “Gen Z.”

“The term Gen Z has been stigmatized in a way,” said one student. “Especially older generations see [someone in] Gen Z as someone who is too sensitive or you can’t say anything to them because they’ll always get offended,” she said.

The students agreed that they don’t want to be labeled.

“I don’t think I fit into one bubble in particular, I think a dabble in a little bit of everything,” another student said.

And yet, while at first the students said they don’t feel like it’s possible to capture an entire generation with a singular set of characteristics, they in turn listed traits that define their generation.

They’re not thin-skinned, just broad-minded, they said, adding that social media exposes them to different viewpoints and perspectives, gives visibility into others’ lives, and provides the ability to collaborate in pursuit of social justice.

“In reality we’re just more open-minded to different issues, and we’re pursuing this idea of equality for all,” said one student.

The students at Dover High (especially those who couldn’t vote) described first-hand experience with civic engagement.

As part of the Black Community on Campus Club, some students advocated for a curriculum that includes more Black history and racial studies. Many said they posted black squares on Instagram during the peak of the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2020 and others had posted about the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. Most of the students had protested or marched in Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

Yet of the three high school students eligible to vote, only one cast a ballot this year.

“I started really getting into politics around five years ago [and was] waiting for the day I was 18. I think voting is the best way for you to use your civic duty,” said the one student who voted.

The two who held back from voting said it was because they didn’t have enough information to make an informed decision.

Overall, the high schoolers said that both online and in school, they see far more information about party politics and polarization than how to vote or what to vote for. They advocated for more civics education, adding that electing to take one AP government class senior year isn’t sufficient.

‘The world’s corrupt. We know that. We get it. But what are we going to do to move forward?’

At DSU, the conversation centered around race and racial disparities.

One young woman said she wants to see “less news stories based on race.”

“The fact that somebody can question what we’re angry about… The news daily can make you angry. You turn on the news, another person is being shot dead. I don’t want to see it… If it’s on social media, I unfollow the page,” she said.

“I’m not angry, I’m frustrated,” said another student. “Personally, there’s a lot going on. The world’s corrupt. We know that. We get it. But what are we going to do to move forward?”

The college students advocated for more mental health resources in schools to help students, particularly for Black students and students of color.

Like the students at Dover High, the group at DSU emphasized that Black history should be taught, in its totality, in the classroom.

As for electoral politics, five of the eight students at DSU voted in the midterms. The conversation escalated when the students explained why they did or did not vote.

One young woman described not voting because she hasn’t seen tangible change since 2020 – she talked about disappointment in her home community of Washington, D.C., where she’s witnessed gentrification and gun violence. She didn’t realize that a chunk of student debt had been cancelled, which some of her peers chided her for.

“I thought that Joe Biden was going to make a difference for the Black community because at the end of the day we need financial support,” she said.

“That stuff is smaller than the president,” said another student. “President Biden can only do so much.”

The discussion shifted toward local issues, and one student suggested that it’s hypocritical to complain about issues in your community if you didn’t vote.

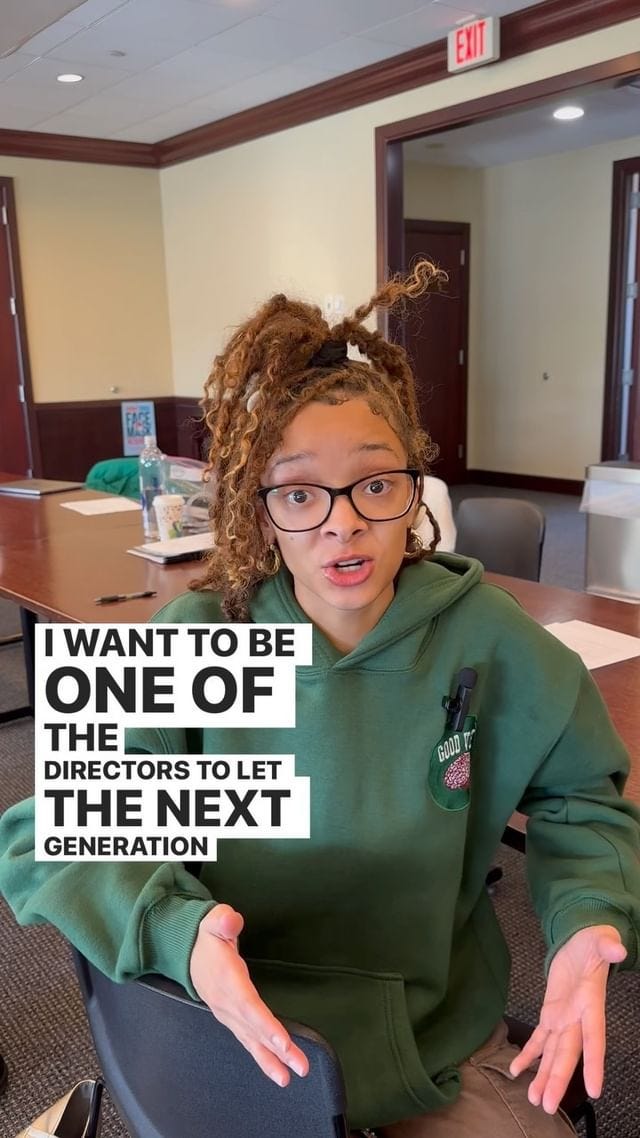

Asked how to create change if not through voting, one student talked about how she’s a content creator who focuses on untold stories from history pertaining to race and ethnicity. Inspired by the Netflix film ‘When They See Us’ about the Central Park Five, she said she wants to become a director in part to “pay homage to our history and why the world is the way it is now.”

Another said she is studying nursing and wants to address the Black maternal mortality rate. She said she hopes to combine the practice of nursing with healthcare policy.

“Going into the older generation, they’re stagnant. We are very progressive and we’re moving forward. I think sometimes they’re resentful of us because of how… with the age of technology and even though we may seem divided at times and that’s what picked out, we’re more connected than ever,” one student said.

“For this generation, we have to come together and find a solution, even if we don’t agree,” said another.

Some reflection

In the month since the midterms, I’ve spoken with nearly 100 young Americans. The early youth vote data confirms a trend of young Americans turning out in relatively high numbers for three election cycles in a row.

We can talk about the power and potential of young voters – but the reality is that there is still such a small portion (about a quarter, according the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement’s early estimate) of young Americans voting.

Often, when I’ve asked a young person why they didn’t vote, they said they were too busy. A few said they couldn’t bring themselves to.

And yet – even though many of these young people didn’t vote in 2022, they are able to succinctly describe the issues in their communities and have clear visions for their futures. They’re optimistic about their power and potential, too.

At risk of overgeneralizing, this generation is fired up about social change.

There are many theories as to why that is. Perhaps it’s a mix of the number and consistency of crises that have colored their lives, social media, and a sense of collective action that comes when you combine those two.

The challenge, however, is that many young people don’t see voting as the vehicle for that change.

In the lead up to the midterms, we talked a lot about youth disillusionment. Many young people I spoke with this fall said they felt like politics didn’t work for them, and they felt politicians only reached out to them when they needed their votes.

I’m still hearing this sentiment on the road. In conversations with young Americans of color both in Delaware and Boston, potential voters said they actively decided not to vote because they don’t see it making any difference in their communities.

And so, the unique opportunity for anyone (regardless of party) who cares about civic engagement or social change, is to help connect those dots for young people.